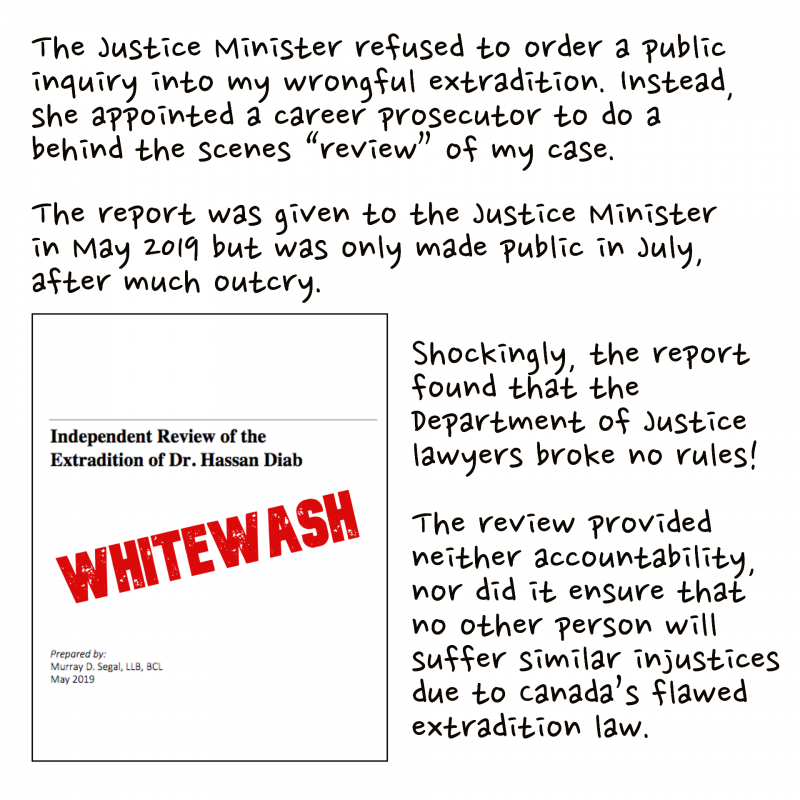

August 9, 2019 (Ottawa)—The International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group (ICLMG) is deeply disappointed with the findings of the external review into the extradition and detention without trial in France of Dr. Hassan Diab. The review was commissioned by the Department of Justice and conducted by Murray Segal, the former Deputy Attorney General of Ontario.

August 9, 2019 (Ottawa)—The International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group (ICLMG) is deeply disappointed with the findings of the external review into the extradition and detention without trial in France of Dr. Hassan Diab. The review was commissioned by the Department of Justice and conducted by Murray Segal, the former Deputy Attorney General of Ontario.

“This review, in finding that Department of Justice lawyers and Canadian officials broke no rules, does nothing to bring justice to the grave human rights abuses suffered by Dr. Diab, or to ensure that no other person suffers similar injustices due to Canada’s flawed extradition laws,” said Tim McSorley, national coordinator of the ICLMG.

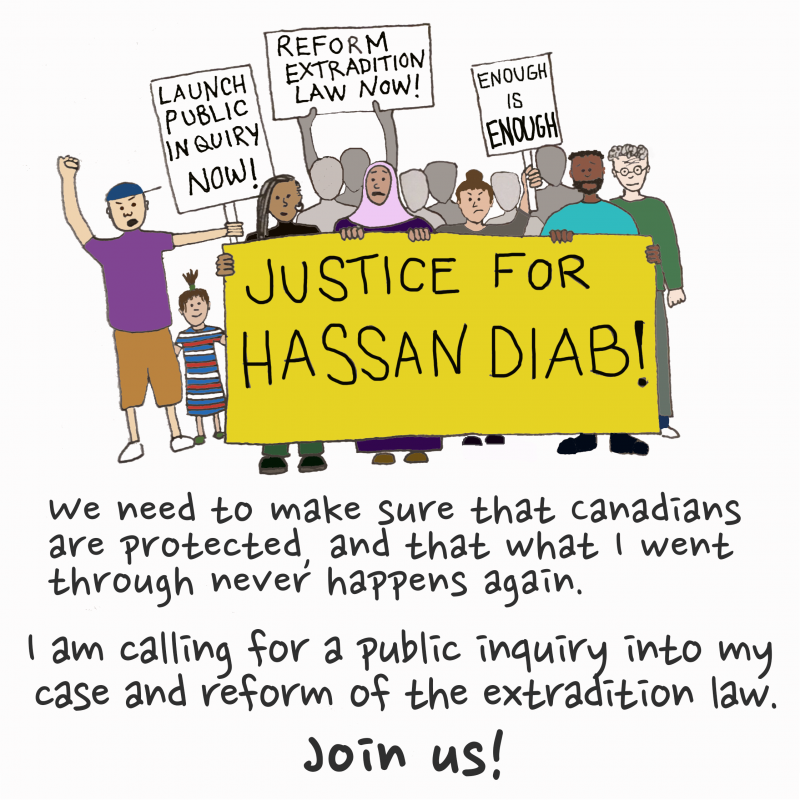

Mr. Segal’s report makes various recommendations for the government to take into consideration, but falls far short of suggesting concrete, legislative changes that are needed to truly resolve these issues. This further reinforces the call from Dr. Diab, his supporters, and various human rights and civil liberty organizations, that the government of Canada must initiate a full, public and independent inquiry into the case of Dr. Diab and Canada’s extradition laws. These groups include Amnesty International Canada, the BC Civil Liberties Association, the Criminal Lawyers’ Association, and the Canadian Association of University Teachers, all of whom have issued calls for an inquiry since Dr. Diab’s return to Canada in January 2018.

“The fact that the report concludes that Department of Justice lawyers did not break the rules provides no solace,” said McSorley. “Rather, it points to the urgent need to address the most troubling aspects of Canada’s extradition laws. The Extradition Act must be changed.”

The ICLMG is particularly concerned with the intersection between Dr. Diab’s extradition and anti-terrorism laws.

“While there is no doubt that governments should seek out to investigate and prosecute the perpetrators of heinous acts like that on Rue Copernic in 1980, we cannot ignore that countries, including France, have introduced troubling laws and have espoused political priorities that undermine the rights of the accused in the pursuit of the so-called ‘war on terror,’” said McSorley.

This includes the growing use during trial of “unsourced intelligence,” the veracity of which cannot be ascertained and which can never be fully verified to ensure it was not obtained through torture or mistreatment. Such information cannot be used in Canadian criminal proceedings, but was originally included in the documents submitted by France for Dr. Diab’s extradition, and is allowable in French courts.

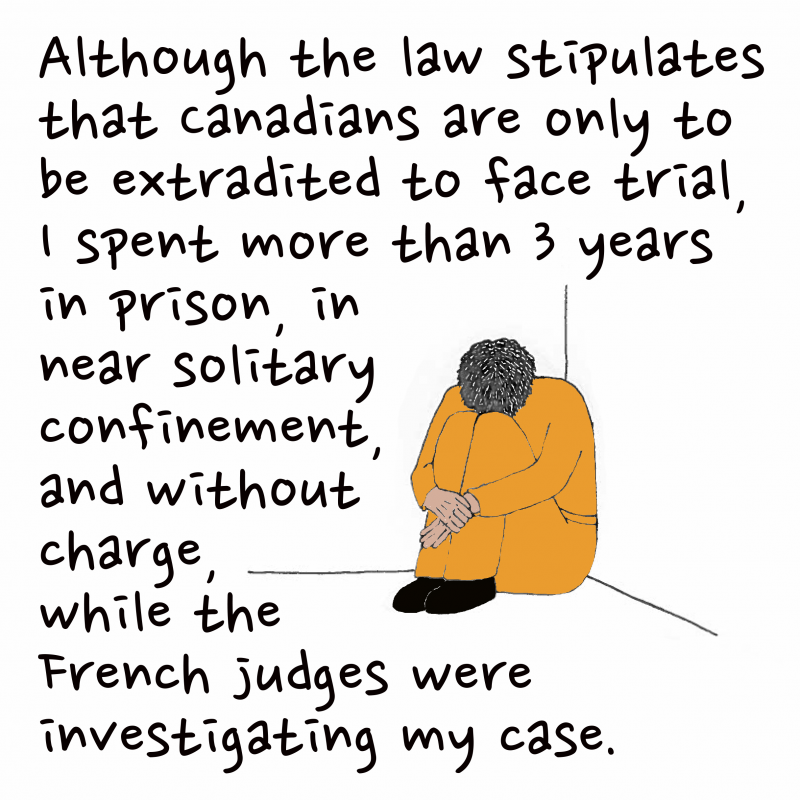

Also of concern is the use of extraordinary anti-terrorism laws that allow for the ongoing and indefinite detention of individuals while they are being investigated, and before they are ever put on trial. This is what led to Dr. Diab suffering in prison for three years in France, often in solitary confinement, before being released when investigating judges decided not to proceed to trial.

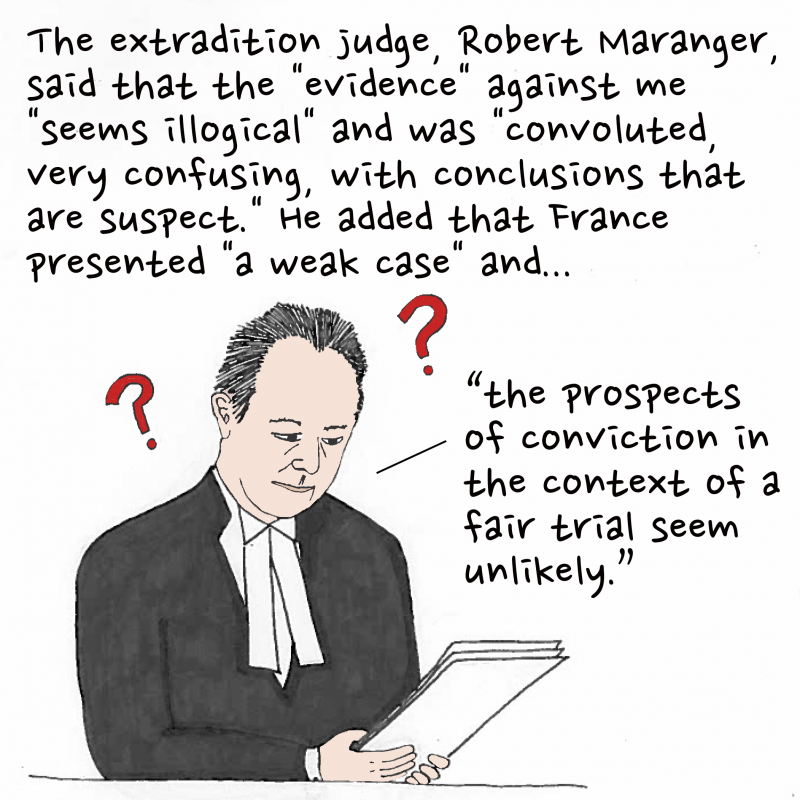

Canadian law ostensibly limits extraditing individuals to trial, and not to investigation. Despite clear warnings from Dr. Diab’s counsel, legal experts and human rights organizations, Canadian courts and government officials ignored the signs that Dr. Diab’s trial would not begin right away and agreed to extradition. The Ontario Court of Appeal went so far as to say they believed that Dr. Diab, “will not simply ‘languish in prison,’” which he did, for three years, at considerable cost.

Finally, we join others in questioning the release of this report two months after being submitted to the Minister of Justice, at the end of July before an election, when little public or parliamentary scrutiny will be placed on it. The release of the report at this time severely undermines the incredibly important and necessary follow-up and questioning that it deserves.

Given these outstanding concerns, it is imperative that the government seeks independent, rigorous investigation of Dr. Diab’s case and of the failings of the Extradition Act through the appointment of a full public inquiry. Nothing less will suffice.

-30-

Contact:

Tim McSorley, ICLMG national coordinator

(613) 241-5298

August 9, 2019 (Ottawa)—The International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group (ICLMG) is deeply disappointed with the findings of the external review into the extradition and detention without trial in France of Dr. Hassan Diab. The review was commissioned by the Department of Justice and conducted by Murray Segal, the former Deputy Attorney General of Ontario.

August 9, 2019 (Ottawa)—The International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group (ICLMG) is deeply disappointed with the findings of the external review into the extradition and detention without trial in France of Dr. Hassan Diab. The review was commissioned by the Department of Justice and conducted by Murray Segal, the former Deputy Attorney General of Ontario.