This piece was published in French in the magazine of la Ligue des droits et libertés.

Written by Tim McSorley, national coordinator, International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group

Over the past two decades, many of us have come to rely on online platforms for basic necessities, for communication, for education and for entertainment. Online, we see the good – access to otherwise hard to find information, connecting with loved ones – and the bad. It often combines the harms we know so well, including hate speech, racism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, the sexual exploitation of minors, bullying and incitement to violence, with new forms of harassment and abuse that can happen at a much larger scale, and with new ways to distribute harmful and illegal content.

Many social media sites have committed to addressing these harms. But business models that focus on retention – regardless of the content we’re being fed – have proven ineffective at doing so. When these online platforms do remove content, researchers have documented that it is often those very communities that face harassment that also face the most censorship. Governments around the world have also used the excuse of combating hate speech and online harms to enact censorship and silence opponents, including human rights defenders.

The Canadian government had been promising since 2019 to address this issue, framing it explicitly around fighting “online hate.” The government eventually released its proposal to tackle online harms in late July 2021, alongside a public consultation. There were immediate concerns with the consultation taking place in the dead of summer with an imminent election on the horizon. When the election was called a few weeks later, round tables with government officials who could answer questions about the proposal were cancelled.

While the government’s approach was bad, the proposal itself was worse. As cyber policy researcher Daphne Keller described it, Canada’s original proposal was “like a list of the worst ideas around the world – the ones human rights groups… have been fighting in the EU, India, Australia, Singapore, Indonesia, and elsewhere.”

What were some of those problems?

First, many groups raised concerns about the scope of the proposal. It attempted to create one regime to address five very different forms of harm – hate speech, the non-consensual sharing of intimate images, child sexual abuse material, content inciting violence and terrorism content – that in fact require very specific distinct solutions. What is effective for one area may be unnecessary, or even detrimental, to another.

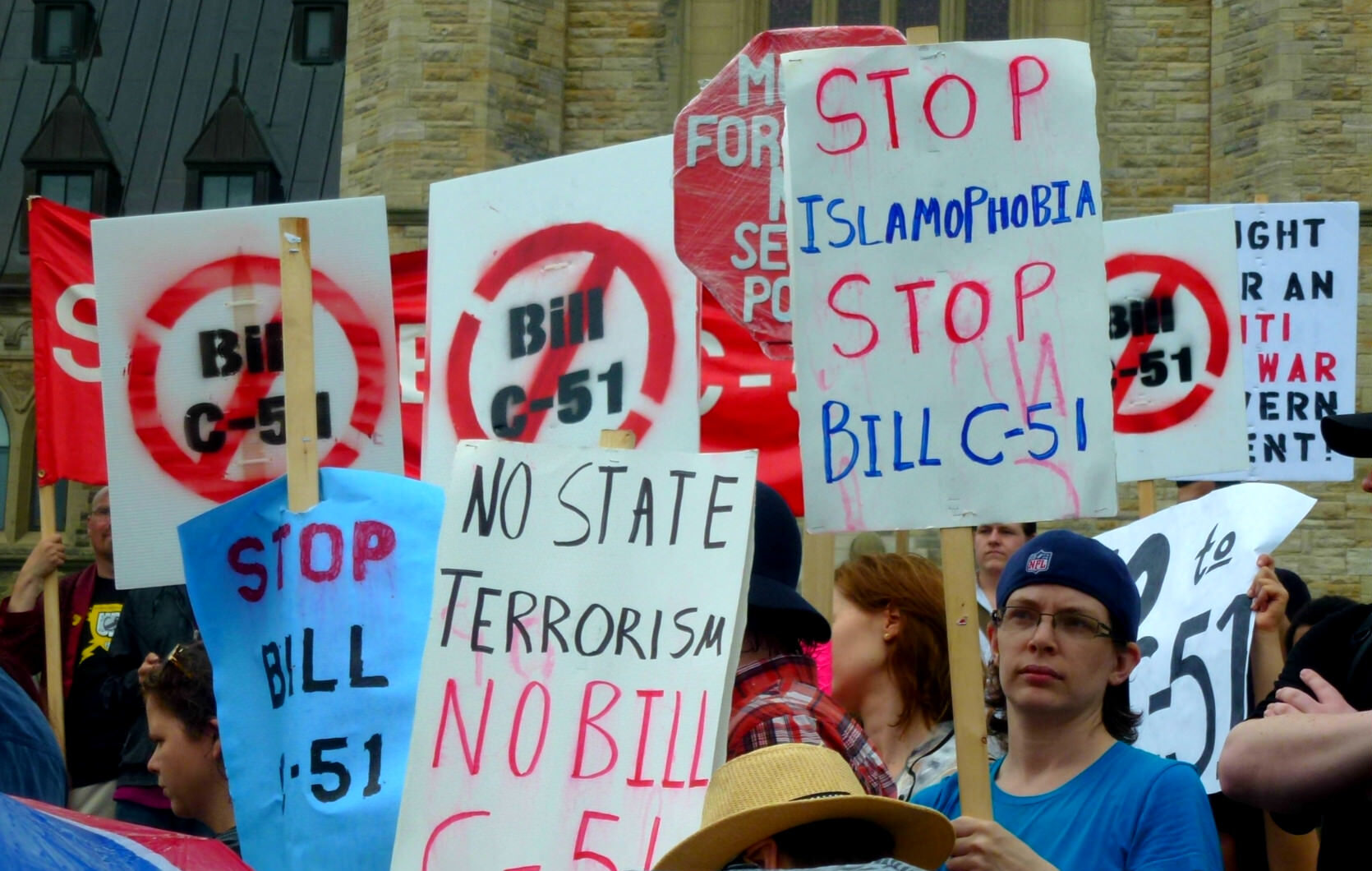

Next, the inclusion of “terrorist content” itself was problematic. Since Canada first joined the “War on Terror” in 2001, we have seen how the enforcement of terrorism laws has led to the violation of human rights, especially because its definition can be twisted to suit political ends. Yet social media companies would be asked to identify it, and on that basis report content and users to the police. It was a recipe for racial and political profiling, particularly of Muslims, Indigenous people and other people of color, and for the violation of their rights and freedoms.

Third, the proposal would have created a vast new surveillance regime, enforced by social media companies. It would require companies to monitor all content posted to their platforms that is visible in Canada, to screen it for online harms, and to take “all reasonable measures” to block the harmful content, including using automated algorithms. Platforms would also need to act on any content reported by users within 24 hours – an incredibly short time frame. Coupled with penalties up to millions of dollars, platforms would be incentivized to take content down first, and then deal with the consequences later. This would create a massive incentive for censorship of controversial – but legal – content.

Fourth, new rules would require platforms to automatically share information with law enforcement and national security agencies, further privatizing the surveillance and criminalization of internet users. This meant that not only would platforms be deciding what content to remove, but who and what needed to be reported to police. As many critics pointed out, further involving the police and intelligence agencies is not a solution when it comes to dealing with harms to groups already facing higher levels of criminalization.

The proposal also made the extraordinary argument, with little justification, that CSIS be granted a new form of warrant to “simplify” the process for obtaining basic subscriber information in order to aid with the investigation of online harms. This comes at a time when courts have been criticizing CSIS for violating the more stringent warrant requirements already in place.

Finally, one of the clear lessons from other countries is the need for rigorous transparency and accountability rules, both for the platforms and for the body enforcing new online harms regulations. Unfortunately, the Canadian government’s proposal did not include meaningful, public reporting and very few transparency or accountability requirements.

Latest developments

In February 2022, the Ministry of Heritage released a “What We Heard” report in which they recognized many of the valid concerns with the government’s approach. They announced a new consultation process led by a new expert advisory group that would review these concerns and propose advice on what the government’s approach should be. Importantly, the process and the deliberations by the group will be shared publicly.

We are now in the very early stages of that process. On one hand, we can see this as a victory: groups from across very different sectors collectively raised concerns about a flawed legislative proposal, and the government has agreed to revisit it. However, an initial reading of the documents guiding the new process sends mixed messages.

The government appears to be conceding that a system based primarily on takedowns and increased surveillance is unacceptable. Background documents also include a greater emphasis on protecting freedom of expression and privacy.

At the same time, they are explicitly building off of a new UK model, found in the proposed Online Safety Bill, known as “duty of care.” While it is based on the idea that platforms must take responsibility for their actions, it has also faced steep criticism for focusing on “lawful but awful” content as well. “Lawful but awful” means content and activity that while legal, may be viewed as harmful. The concern is that platforms would not only be required to identify whether content is illegal – which can already be difficult – but also whether content that is legal should be considered harmful. This vagueness would likely lead to even broader content removal and censorship.

Along with the new approach, the idea of addressing the same five harms under one system persists, and while worded differently, mandatory reporting to law enforcement remains.

Various groups, including the ICLMG, continue to work together to respond to the government’s proposals and to develop ideas on how best to fight online harms. This is clearly a complex problem, and it is easier to point out flaws than to develop concrete solutions. What appears clear, though, is that empowering private online platforms to carry out greater surveillance and content removal would not only fail to address the heart of the issue, but would create more harm. Instead, governments must invest in offline solutions combatting the roots of racism, misogyny, bigotry and hatred. Just as importantly, governments must address the business models of social media platforms that profit from surveillance and use content that causes outrage and division as a way to drive engagement and to retain audiences. So long as there is profit to be made from fuelling these harms, we will never truly address them.

Since you’re here…

… we have a small favour to ask. Here at ICLMG, we are working very hard to protect and promote human rights and civil liberties in the context of the so-called “war on terror” in Canada. We do not receive any financial support from any federal, provincial or municipal governments or political parties. You can become our patron on Patreon and get rewards in exchange for your support. You can give as little as $1/month (that’s only $12/year!) and you can unsubscribe at any time. Any donations will go a long way to support our work. You can also make a one-time donation or donate monthly via Paypal by clicking on the button below. On the fence about giving? Check out our Achievements and Gains since we were created in 2002. Thank you for your generosity! You can also make a one-time donation or donate monthly via Paypal by clicking on the button below. On the fence about giving? Check out our Achievements and Gains since we were created in 2002. Thank you for your generosity!

|