Dear ICLMG members and supporters,

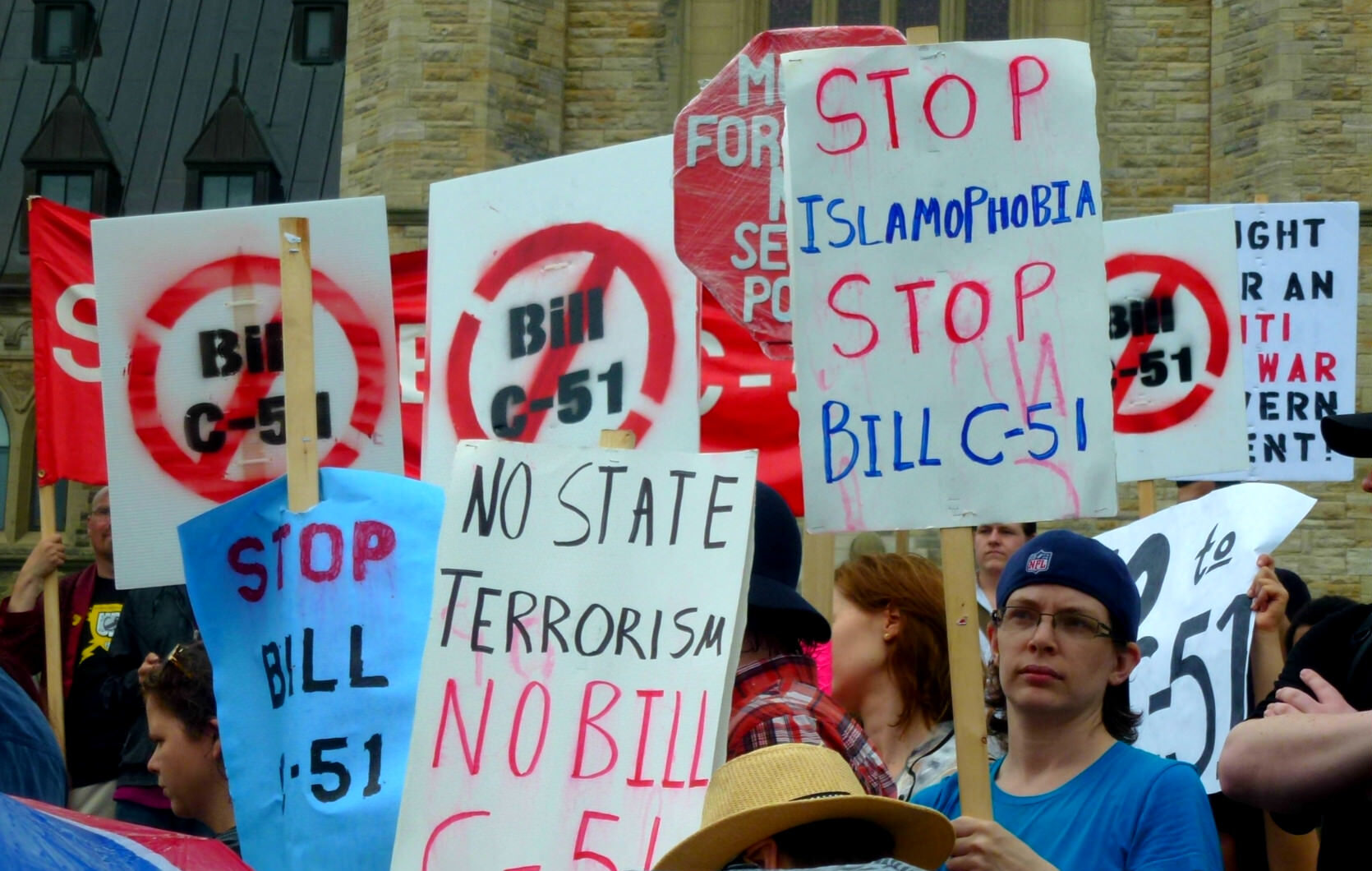

Parliament is back with a packed agenda and a new leader of the official opposition with a track record of supporting some of the most regressive anti-terrorism laws in Canadian history.

Our small team has been hard at work monitoring national security activities, defending civil liberties and preparing for parliament’s return, but we can’t do it without you.

There are some key bills and legislative proposals that we’ll be taking on this fall:

- Protecting our Privacy at the Border (Bill S-7)

- Independent Review for the CBSA (Bill C-20)

- Protecting our Privacy in the Private Sector and Regulating Artificial Intelligence (Bill C-27)

- Online Harms and the Fight Against Expanding “Anti-terrorism” Powers (upcoming legislation)

Our small team is working to defend civil liberties. Can you help us make it happen?

WHY ARE THESE BILLS IMPORTANT?

Protecting our Privacy at the Border (S-7)

Earlier this year, we had an important victory when our advocacy efforts secured amendments to a new border search bill, known as S-7. These amendments will help protect the private information on our cell phones and laptops at the border. We successfully argued to the Senate to do away with a new, incredibly low threshold proposed by the government that would have allowed border agents to search electronic devices on a whim, in favour of a stronger, known standard.

This fall, S-7 will be coming to the House of Commons for debate and study by MPs, and the government could try to reverse the Senate improvements in favour of their original plan. We’re preparing to continue the fight to make sure the stronger standard sticks and that we don’t need to worry about excessive snooping when travelling to Canada.

Independent Review for the CBSA (C-20)

Before the summer break, the government introduced Bill C-20, which would reform the RCMP’s current review body and expand it to also include the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA). Independent review of the CBSA is desperately needed, and has been a priority in our coalition’s advocacy work. But this is the third CBSA review bill proposed by this government, with the other two never making it further than second reading. We need to make sure that independent review comes to the CBSA, and we need to make sure it’s done right. We’ve convened a network of groups to develop proposals for strengthening the bill, and will be bringing our concerns to MPs and the government this fall.

Help us in the fight to protect privacy, civil liberties and human rights.

Protecting our Privacy in the Private Sector and Regulating Artificial Intelligence (C-27)

In the coming weeks, Bill C-27 will also be back before MPs. This massive piece of legislation will update Canada’s laws regulating how the private sector handles our personal information. Unfortunately, it keeps in place broad loopholes that allow companies to collect, use and disclose our personal information on vague “national security” grounds. It also proposes sorely needed rules for regulating the use of Artificial Intelligence in the private sector. Surprise, though: it exempts all AI tools under the “direction or control” of Canada’s national security and defense agencies from these new rules. This is unacceptable, and we plan to be at the forefront of closing these loopholes and putting privacy and rights protections first.

Online Harms and the Fight Against Expanding “Anti-terrorism” Powers

While not yet a bill, the government is gearing up for legislation to regulate content online to prevent the spread of material that incites hatred or violence and that causes harm. We believe in greater accountability for social media platforms on how they operate and profit from material that promotes racism, violence, misogyny, homophobia and transphobia. Unfortunately, the government’s original proposal would have introduced new, broader definitions of “terrorist content;” deputized social media platforms to surveill all content uploaded to their sites and require them to report back to law enforcement and intelligence agencies; and granted broad new warrant powers to CSIS. We helped to force them back to the drawing board, but with new legislation likely coming in the next few months, we need to keep up the pressure.

We’ve had successes, but there’s much more to do!

We’re also hard at work on many other issues we’ll update you about in the coming weeks, from the urgent need to repatriate Canadians in indefinite detention in life-threatening camps in North Eastern Syria, to the fight against security certificates and justice for Mohamed Harkat, to CSIS’ involvement in unlawful activities and misleading the courts, and the ongoing problem of the No Fly List and the CRA’s prejudiced audits of Muslim charities. Plus, we’ll have news about celebrating ICLMG’s 20th anniversary. Stay tuned!

Thank you in advance for your essential support in protecting and promoting civil liberties!

In solidarity,

Tim & Xan