On Friday, April 30th, the Intelligence Commissioner (IC) tabled his 2020 Annual Report in Parliament. To date, there has been no media coverage of the reports findings, although ChrisParsons, senior research associate at the Citizen Lab, and Leah West, assistant professor of national security law and counterterrorism at Carleton University, have both posted some important insights into different aspects of the report on Twitter, here & here.

The lack of coverage isn’t necessarily surprising: A late Friday release often means minimal coverage. Urgent coverage of COVID-19 related news, focus on the train-wreck of Bill C-10, and ongoing parliamentary debates of the recently tabled budgets also helped overshadow the report.

There is also the fact that there doesn’t appear to be a bombshell finding in the report, with the IC writing that, “both [Public Safety and National Defense] ministers, as well as CSE and CSIS, displayed a continuous commitment to improving their processes and submissions, despite the challenges and the burden of the pandemic.” (The CSE is the Communications Security Establishment, which collects foreign signals intelligence, and CSIS is the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, our country’s domestic intelligence agency).

CSIS determinations and authorizations for 2020, from the Intelligence Commissioner’s 2020 Annual Report.

Overall, the IC approved all authorizations for CSE foreign intelligence and cybersecurity activities, as well as all authorizations and determinations for CSIS datasets and acts or omissions that would otherwise constitute an offence. Based on that alone, it would appear there is nothing of concern and we can all just move on.

But the approvals of the IC are based upon the reasonableness of the decisions. And while he found all the authorizations and determinations to be reasonable, he goes on to point out some “opportunities for improvement” in most areas that deserve closer examination. These are areas where potentially deeper problems could arise. To those of us who are critical of current government surveillance powers, some of the issues may appear more concerning than how the IC presents them (although oversight bodies are known for their understated language). There is also the question of what doesn’t appear in this report, through no fault of the IC, revealing the weaknesses in the reporting and review system in place.

CSIS Foreign Dataset Authorizations raise questions

Both West and Parsons focus in on issues regarding the CSIS director’s authorization of the retention of a Foreign Dataset. Some background: Since 2019, CSIS has been allowed to collect foreign datasets; once collected, the service must request authorization from either the Minister of Public Safety or from a designated individual (currently, the director of CSIS) to retain that dataset. The Intelligence Commissioner must then approve this authorization, or the dataset must be destroyed.

In 2020, CSIS submitted one authorization for retention of a foreign dataset, which the IC approved. But in his findings, he pointed out a troubling loophole that West looked at a little more deeply: CSIS had collected this foreign dataset in 2019 and submitted it to the Director for authorization to retain it within the necessary 90 days. However, the CSIS director then sat on that request, and only authorized the retention more than a year later, in November 2020.

The authorization was only then submitted to the IC for approval. As the IC points out, there is no legislated timeline for the CSIS director, as the designated decision maker, to issue a decision on authorization. During that time, CSIS is also not allowed – under normal circumstances – to use the information contained in that dataset. However, as West points out, CSIS could make a request for exigent reasons to have access to and use the information in that dataset. While this did not happen, it raises serious concerns that a dataset that has not been authorized or approved could be held onto, in a kind of limbo, until such an exigent circumstance arises or until the security situation changes and the argument for authorization becomes more conducive to approval. While it’s impossible to definitively assess the reason for this long timeline, the IC points out that the director was actively considering whether authorization was appropriate throughout the year, and the pandemic hit during this period too. Even given these reasons, though, this situation underlines a potential weakness that needs to be addressed. As West suggests, it should be fixed when the National Security Act (previously known as Bill C-59) comes up for review next year.

Also in relation to foreign dataset retention, the IC states that insufficient or even non-existent information in the CSIS authorization meant he was forced to “[defer] to the Director’s expertise concerning the handling of dataset backups, as well as his expertise in determining that the information contained in the dataset would likely assist CSIS in the performance of its duties and functions.”

Parsons rightly characterizes this as “unsettling” and asks, “Does the IC not require CSIS to clearly explain how datasets will be useful before approving their retention and use?” This is especially important given that the secrecy of this authorization and approval process is meant to be counter-balanced by independent, third party and quasi-judicial oversight. If even the IC is not being provided a complete record and must “defer” to the expertise of the CSIS director, it raises important questions about the effectiveness of these safeguards.

The Mystery of the Disappearing Canadian Datasets.

Finally, on to the mystery of the disappearing Canadian datasets.

First, no Canadian datasets have been lost. But what has disappeared is any information about if and how these new powers are being used. It reveals a significant gap in transparency and raises some important questions.

One of the powers granted to CSIS under the new dataset regime is the collection, retention and use of Canadian datasets: information about Canadians or people in Canada that is not directly related to a threat to Canada, but that is “relevant” to CSIS’s activities. (ICLMG has raised concerns with this new dataset regime overall, which you can read here).

The approval process is similar to that for retention of foreign datasets. The Minister of Public Safety determines the classes of datasets that can be collected, and the IC must then approve that determination before any collection is allowed. The determinations from the minister last at most one year.

The process differs with regards to retention, though. While the IC approves the retention of foreign datasets, CSIS must seek judicial authorization from the courts to retain a Canadian dataset.

In his 2019 report, the IC stated he approved one determination allowing for four classes of Canadian datasets to be collected. It’s important to note that since the 2019 determination was made partway through the year, it would only expire sometime in 2020. However, the IC reports he did not receive any requests for approval of classes of Canadian datasets in 2020. This raises the seemingly odd question of whether or not, following the expiry of the 2019 determination, CSIS maintained the ability to collect any Canadian datasets. This is highly surprising, since a primary argument in favour of granting CSIS the power to collect datasets was the necessity of this tool to effectively accomplish its work.

We also don’t know whether CSIS actually collected any Canadian datasets under the 2019 authorizations, whether it requested to retain any of the Canadian datasets it may have collected, or whether the courts approved the requests or not. This is because the Intelligence Commissioner plays no role in the retention approval process, and so is not able to report on them. In essence, after 2019, the trail of Canadian datasets goes cold.

While not obliged to, the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) did report on CSIS’ requests to the court to retain Canadian datasets in its 2019 Annual Report, and found that no such requests were made that year. It is positive that NSIRA took this on, but it is not obliged to, and there is no guarantee it will be covered in future years. It may not even be under NSIRA’s control: for NSIRA’s 2019 report, the agency was not able to report on the number of ministerial authorizations granted to the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), because the CSE viewed that releasing such numbers would be injurious to national security. To NSIRA’s great credit, they still included a table with Xs in the place of numbers, and explicitly stated their disagreement with the CSE over its withholding of important information. But there is no guarantee that NSIRA will win in this struggle, nor that CSIS won’t make a similar argument in the future, especially if the number of requests to the court rises above zero.

The last point on this is that if CSIS did collect any Canadian datasets, they would have had 90 days to submit a request to the courts to retain them, so it is entirely possible that datasets were collected towards the end of 2019 (especially since the new regime only came into effect in July 2019), and that the requests to the courts for retention only needed to be submitted in 2020 (and therefore were not covered in NSIRA’s 2019 report). Hopefully we will find out more in NSIRA’s 2020 Annual Report, if they are allowed to share the numbers.

What does it mean that the Intelligence Commissioner did not approve any new classes of Canadian datasets in 2019? We can only speculate, but a few options are:

- CSIS, and the Minister of Public Safety, did not deem it necessary for CSIS’ work to collect more Canadian datasets. As mentioned earlier, this would be very surprising, if only because authorizing the classes of datasets that can be collected simply grants the power for CSIS to collect these datasets if need be.

- If the 2019 authorizations expired towards the end of 2020, it’s possible that there was a delay in authorizing new classes of datasets until early 2021, or that the IC’s approval process started in late 2020 and spilled over into 2021. We therefore wouldn’t see them yet. It also would create the unfortunate situation that these approvals would only be reported on a full year after being made.

- Under the same new regime, CSIS can also collect publicly available datasets. These do not need to be independently approved, so there is little reporting on them. It is possible that these are proving of great interest to CSIS, reducing the need to authorize new classes of Canadian datasets. This would be surprising, but still possible. The collection and use of publicly available datasets has faced significant criticism, and makes it all the more important that there should be mandatory reporting on CSIS’ use of them. Again to its credit, NSIRA has promised to take a deep dive into the issue of datasets in the future.

Why is any of this important?

The collection of Canadian datasets is one of the most powerful new tools granted to CSIS with the adoption of the National Security Act in July 2019. It is part of a significant shift that allows intelligence agencies to not just collect information that is related to a national security threat, but troves of unrelated information that is simply relevant to their work that they can analyze and sift through in the hopes of identifying links to existing threats, or new and emerging threats. It also means that more and more of our private information is collected and used in secret, being analyzed with algorithms we don’t have access too, leading to conclusions that are not publicly shared or challenged. Agencies that operate in secret can make mistakes, can over-reach, and can even abuse the system. The main way light gets shed on these issues is through third party reporting, either via the courts, review and oversight agencies or the media. Without a clear thread to follow, especially when new powers are being first brought into existence, it is impossible to catch and fix these problems.

We will need to wait and see if this information is included in NSIRA’s 2020 annual report. That will just be a stop gap though: there must be a clear obligation for at least one body to report – publicly – on the result of CSIS’ collection and retention of Canadian datasets.

Other items of note in the IC 2020 Annual Report

Otherwise unlawful acts or omissions: Possible fodder for a whole other discussion is that the Intelligence Commissioner reports approving seven classes of acts or omissions that would otherwise constitute an offence that CSIS is allowed to engage in. Also brought in with the NSA, this regime allows the Minister of Public Safety to determine classes of otherwise unlawful activities that designated CSIS employees, as individuals operating under CSIS’ direction, can engage in, in relation to intelligence gathering or threats to the security of Canada. The Minister of Public Safety must issue a public report on these activities every year, so we will find out more in the months to come. We know, however, that the IC approved seven classes in 2019 as well, so it may be likely that they were simply renewed.

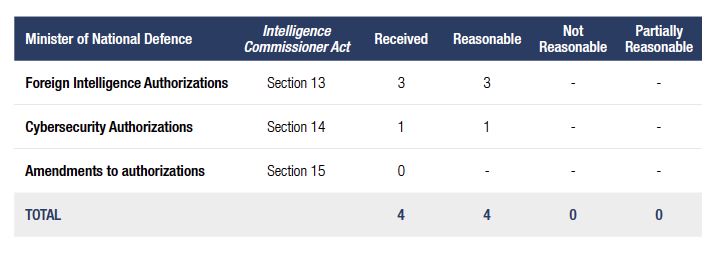

Reporting on the CSE: I’ve only covered CSIS here, but the IC also approves Foreign Intelligence authorizations and Cybersecurity authorizations made by the Minister of National Defence in regards to the CSE. In 2020, the IC approved three Foreign Intelligence Authorizations and one Cybersecurity Authorization. Bill Robinson, Citizen Lab Research Fellow and probably the foremost expert on the CSE in Canada, has a great Twitter thread exploring those authorizations and important questions about them, so I won’t go into them, but I encourage you to read it.

Since you’re here…… we have a small favour to ask. Here at ICLMG, we are working very hard to protect and promote human rights and civil liberties in the context of the so-called “war on terror” in Canada. We do not receive any financial support from any federal, provincial or municipal governments or political parties. You can become our patron on Patreon and get rewards in exchange for your support. You can give as little as $1/month (that’s only $12/year!) and you can unsubscribe at any time. Any donations will go a long way to support our work. |